The Case for Exams

Since time immemorial, examinations have been used as a measure of academic success. Ancient Chinese folklore tell many tales of country youth, in their abiding desire to better themselves and their fates, head to the then-capital of Peking to sit the Imperial exams, to join the ranks of the elite Government.

We all know, examinations are really not the best measure of how well or how much one learns, nor does it come even close as a measure of how intelligent or clever a person is, yet we find, time and time again, that this is the only measure of academic achievement that we fall-back on to. So why do we do it?

As a former academic, having been involved in setting rigorous, externally validated exam questions, I completely agree with all the disadvantages of the examination system, yet there still exists some valid reasons why exams continue to serve as the main measure of academic achievement.

A base line knowledge for everyone

When the Victorians in the Industrial Age (read Peter Gray’s History of Education: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/freedom-learn/200808/brief-history-education) introduced the concept of education for all, making school attendance for children below a certain age compulsory, they also needed a measure of how successful their methods were.

So tests and other measures were put in place. These were perhaps not the same as we know them today but still they were designed to determine whether or not a child had mentally retained the required information. Verbal chanting, spot question and answers, the whip and paddle may have given way to multiple choice, essay questions, bonus topics and compounded test scores – ultimately they are all still an overall measure of how much information has been memorised.

So the truth is, of course, how well one memorises is in no way a measure of how clever a person is, but still it’s be used because ultimately it is the most convenient tool to identify and as far as possible, ensure, a baseline, or a core base of knowledge for each student.

Not a measure of ‘cleverness’ but of competency

Beyond examining for a baseline of knowledge, examinations offer an insight in the the overall competency of the student in a given subject. It would stand to reason that a student with a better exam score would in the overall sense have a better grasp of the subject. It may not always be true, particularly for subjects in which tests follow a rigorous, narrow marking grid, but for a number of subjects, it is indeed the case.

For example, in medical biology, the purpose and action of the sphincter muscle at the end of the duodenum is a ‘need to know’ piece of information that relies solely on being memorised. This of course, is what Academics typically term ’shallow learning’.

Shallow versus Deep Learning

Shallow learning, learning (or memorising) exactly what is necessary to fulfil examination requirements – this may not be the formal definition of shallow learning, but it is certainly apt in that, it is learning, not driven by curiosity but by an external requirement.

Much has been written, researched and said about deep learning; that driven, sometimes innate, always hungry curiosity that makes for an insatiable thirst of knowledge in a particular field. Deep learning is often accompanied by a great desire to find out more, to know, to embed and embody the knowledge and information.

This is clearly not the typical, nor a possible response to the vast ‘touch and go’ range of topics and syllabi that most education systems attempt to cover in a limited frame of time. The ‘jack of all trades’ and ‘master of none’ approach is typically used in an effort to provide as vast a spectrum of knowledge as possible, caring little if the topic is of interest. The purpose of course is to allow students to have a varied taste of possibilities, to account for a ‘core’ syllabus’ in which one can count on as being ‘competent’.

The fact is in learning as much or as broadly as possible is meant to give rise and give way to more specialised knowledge as one reaches higher in the academic process. General schooling gives way to streamed subjects at high school level, undergraduate degrees give way to very specific fields of study at doctoral level.

Rightly or wrongly the idea of a broad education provides opportunity to experiment and find out one’s natural inclinations or tendencies and often leads to the the identifying of preference. This often serves as the foundation of further study.

A foundation upon which to build

A true foundation in a subject often comes from a rigorous knowledge that has been deeply embedded, the ability to call or recall pertinent information at exactly the right moments is often required as one progresses through higher levels of study.

At higher levels of study, it is also within the examination environment that we identify the depth of one’s knowledge and ability in a certain subject. Of course, the case for such ‘drawing out’ is also greatly dependent on the method and style in which the examination questions are set.

In many examinations, questions are usually set in a progressive manner, in which it takes a core knowledge to answer the most basic questions that then lead on to further in-depth questions that subsequently lead on to questions that require an analytical and reflective thought process.

Of course these types of exams are atypical at lower levels of schooling, and require both knowledge and expertise in a subject, along with experience to build and create such an examination paper. However, there should always elements of these stages in all examinations, often to be used as a differentiator, which brings us on to the next point.

More time?

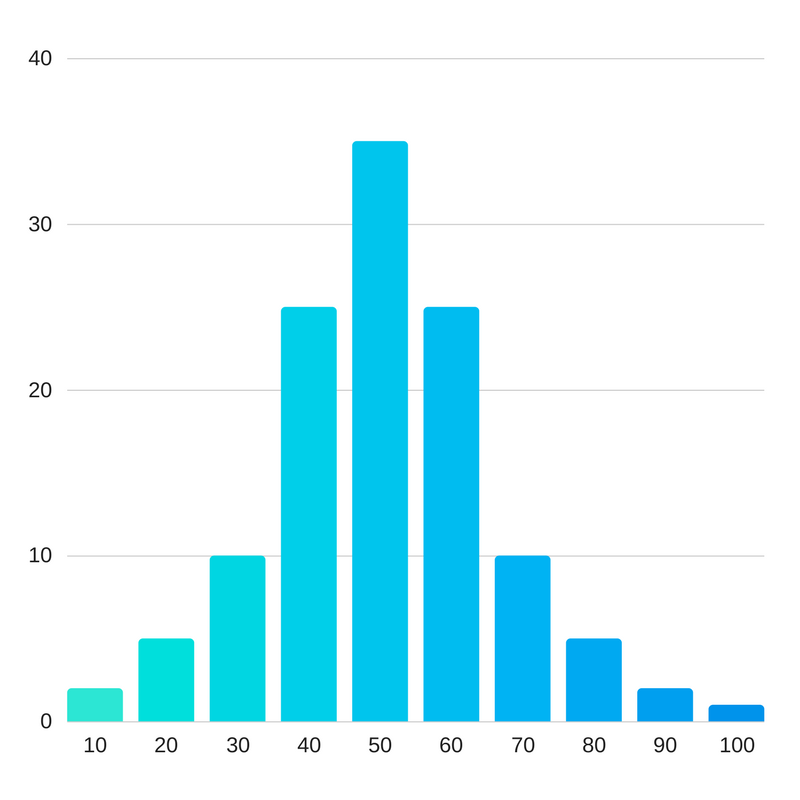

Many students believe ‘if only they had more time’ they would do better. The fact is, at the other end of the exam, as an examiner, it is intriguing to note that the ‘Bell curve’ (normal distribution) is actually quite an accurate representation of exam results.

The curve may be skewed further along to the right, providing a higher average grade if more time were given for an examination paper, but if the exam paper was set correctly, there typically is always a small number that will perform significantly higher than average.

Getting to that ‘pass’

For the majority of students, a ‘pass’ is all that is required to get through. This may not be the aim for some, but for many, this is all that is required. A stepping stone on to the next level. While it certainly does help, to do well and score well, it must be accepted that examinations are a means to an end and not the ‘end’ in themselves.

In short, exams are meant to ‘get you somewhere’, that somewhere lies beyond the realm of examinations, but they serve to provide a stepping stone on the journey towards the destination.

Moving on

Ultimately, exams serve a purpose and a function, they provide a quick insight and a means (especially for teachers) to be able to identify the successful and weaker areas of their own teaching and on a greater scale the overall picture of how well the syllabus works.

While it is gratifying to be able to achieve outstanding scores, strings of As and probably entrance in to prestigious universities based on their results, examinations come no where close to being representative of the individuals who sit them.

Ultimately

To all students out there: Aim for the moon and even if you miss you’ll land among the stars.

To all the teachers out there: Exams are a great tool, but they are only one of many that tell you of a single aspect of a multi-dimensional, interesting exciting individual, Believe in the capabilities and potential of each one, no matter what the red ink says.

To all the policy makers: Exams may seem like the end game, but learning is truly a long game – life-long in fact. It is definitely NOT a competition regardless of what PISA says. Your future is held within the future generations of your country, different shapes make for a far more exciting future than trying to stuff round pegs in to square holes.

How To Ace That Exam: Optimising Learning – Colour My Learning

July 10, 2017 @ 9:09 am

[…] The Case for Exams […]